Short-lived Branches and Conflict Phobia

Originally published on Medium • 4 min read

The Problem: Fear of Merge Conflicts

There’s widespread, unfounded fear surrounding merge conflicts in software development. In traditional non-CI, non-trunk-based development, long-lived branches create conflicts that are difficult to resolve. This leads to the mistaken belief that changes must be carefully isolated from each other.

The reality? This isolation actually creates more problems.

The Misconception

Many teams believe frequent merges are made to “avoid” conflicts. This is backwards thinking. Just like in real life, conflicts are inevitable. The total impact of conflicts isn’t reduced by delays—that’s wishful thinking. The solution is meeting them head-on early, before they grow larger.

Understanding Merge Conflicts

Git’s official documentation explains it clearly:

During a merge, when both sides made changes to the same area, Git cannot randomly pick one side over the other, and asks you to resolve it by leaving what both sides did to that area.

In essence: Git looks at textual changes made by both branches since their common ancestor and attempts to combine them. That’s it—nothing more sophisticated.

Two Types of Conflicts

1. Textual Conflicts

These are what Git detects—when the same lines of code are modified by different branches. These are relatively easy to resolve.

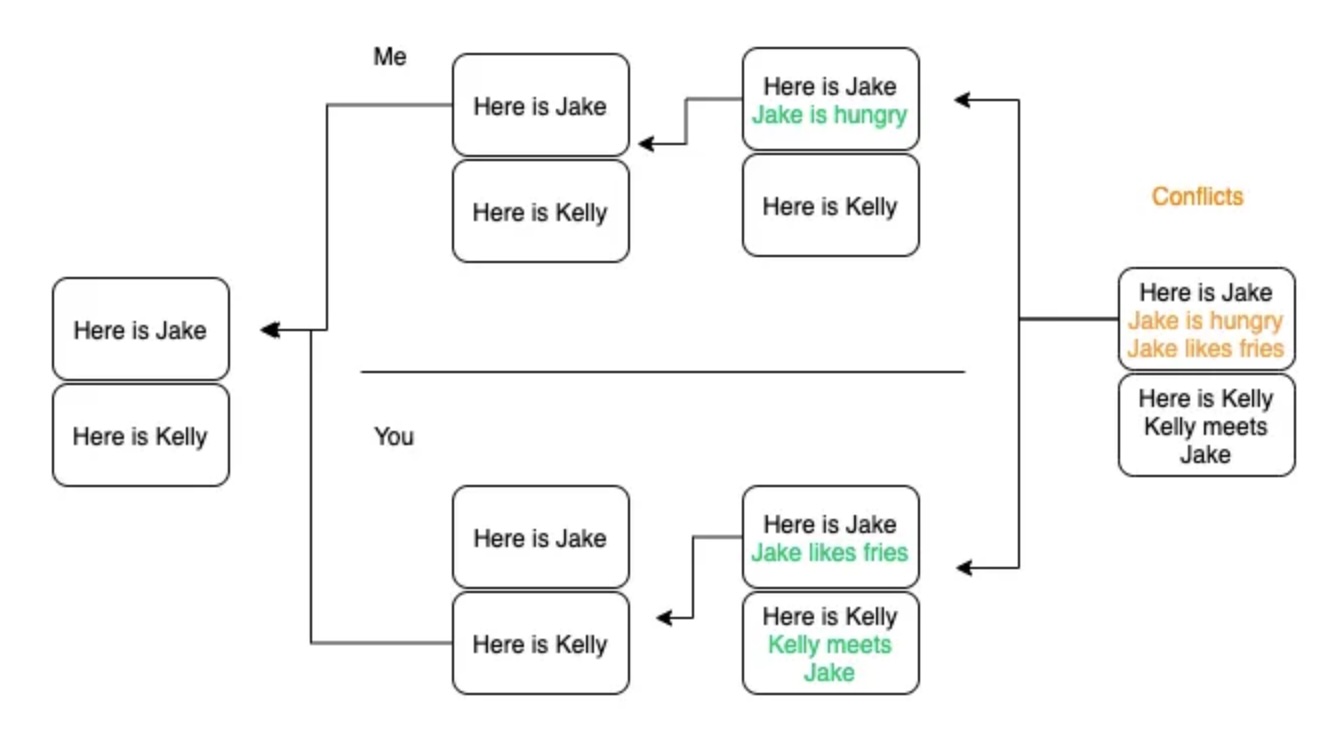

Example of a textual conflict that Git can detect and flag for manual resolution

Example of a textual conflict that Git can detect and flag for manual resolution

2. Semantic Conflicts (The Real Danger)

Consider this scenario: We’re collaborating on a story where Jake is introduced in Chapter 1 and Kelly in Chapter 2.

- I make Jake die at the end of Chapter 1

- You make Kelly meet Jake in Chapter 2

Git merges both changes without conflict, creating a logical impossibility—Kelly cannot meet a dead Jake.

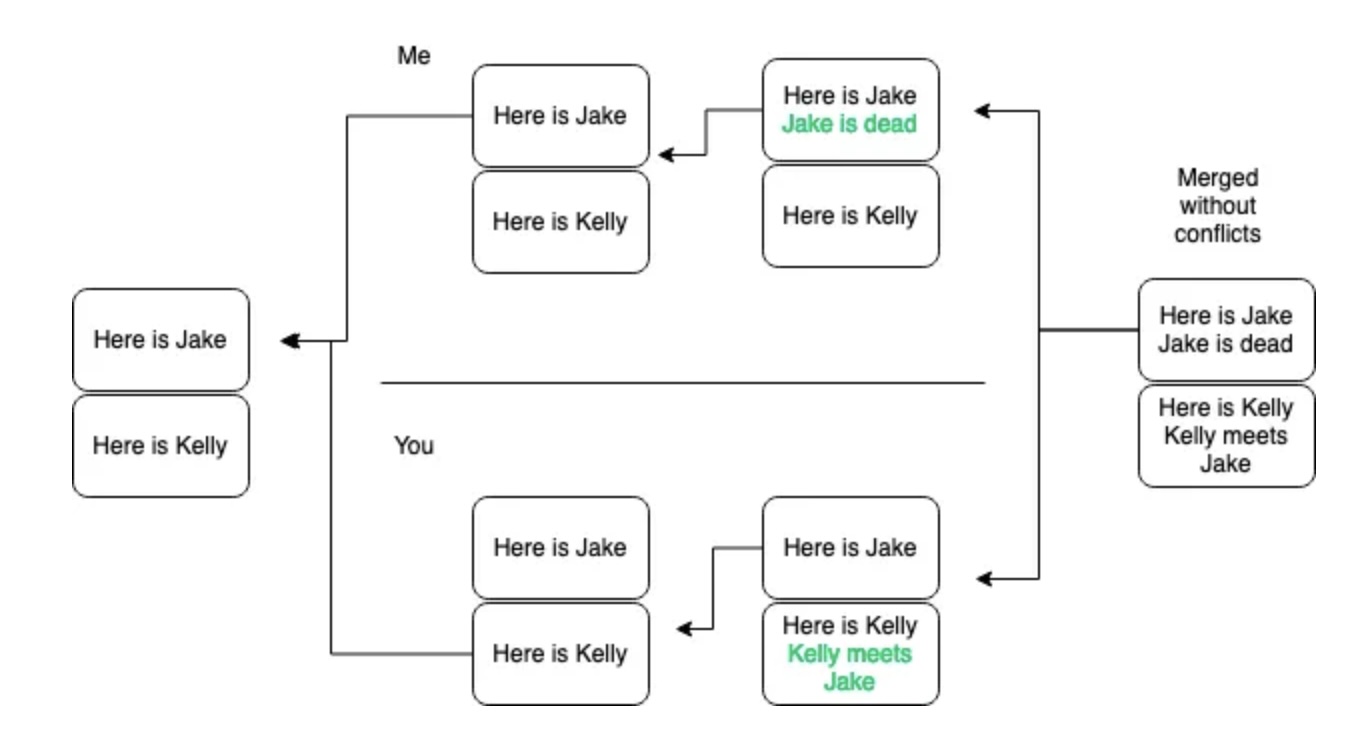

A semantic conflict: Git merges successfully but creates a logical impossibility where Kelly meets dead Jake

A semantic conflict: Git merges successfully but creates a logical impossibility where Kelly meets dead Jake

No automated tool can detect semantic conflicts. These require human judgment and are what we should really worry about.

This is why automated tests are crucial—they capture intended behavior and constraints, alerting us to violations before or after merging.

Why Conflicts Are Unavoidable

Git can raise merge conflicts even when changes are compatible and intended. If two developers modify the same area of code for legitimate reasons, there’s no way to avoid this conflict.

Definitely not by encouraging isolation. The scope of conflicts will compound over time, and eventually, no one will have the confidence to resolve them.

The Solution: Embrace Continuous Integration

Understanding how Git merges leads to one logical conclusion: avoid long-lived branches and git-flow style feature branching.

Best Practices:

- Trunk-based development with automated tests

- Continuous feedback through frequent integration

- Pull from trunk extremely frequently

- Run tests on every commit

- Merge extremely frequently

Key Insights

The Vicious Cycle

A dangerous pattern exists in many organizations:

graph TD

A[Deltas get bigger] --> B[Risk gets bigger]

B --> C[Bad thing happens]

C --> D[More process]

D --> E[More delay]

E --> A

style A fill:#ffeb3b

style B fill:#ff9800

style C fill:#f44336,color:#fff

style D fill:#ff5722,color:#fff

style E fill:#d32f2f,color:#fff

The cycle perpetuates itself: each attempt to reduce risk through process actually increases risk by encouraging larger, less frequent changes.

The Better Approach

Conflicts are just another type of risk. Since risks are better managed when changes are kept small and frequent, the same principles apply:

- Small diffs

- Trunk-based development

- Frequent integration

The contrast between deployment patterns illustrates this perfectly:

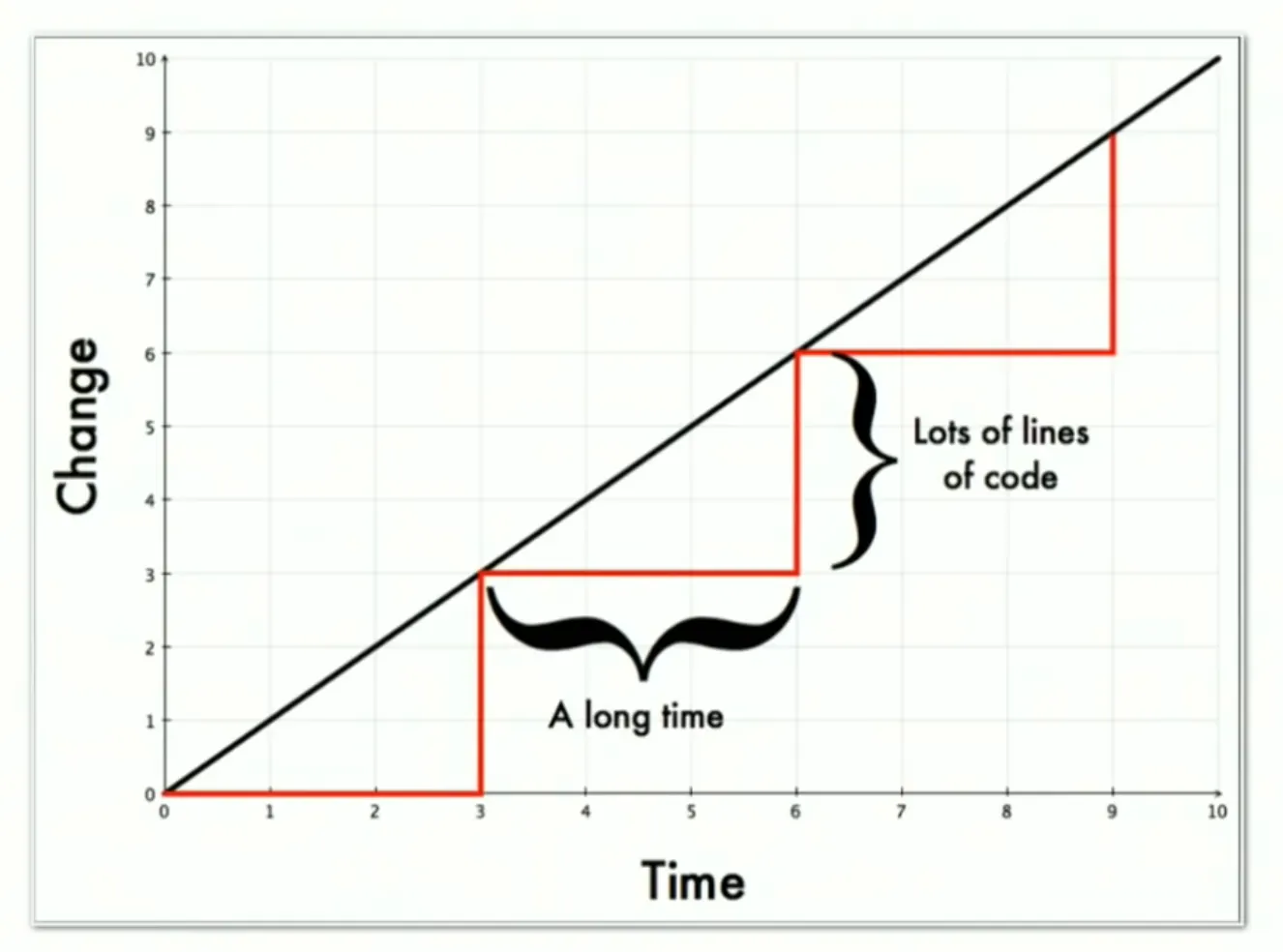

Traditional Approach:

Large, infrequent deployments create massive deltas with long periods of accumulating changes

Large, infrequent deployments create massive deltas with long periods of accumulating changes

Better Approach:

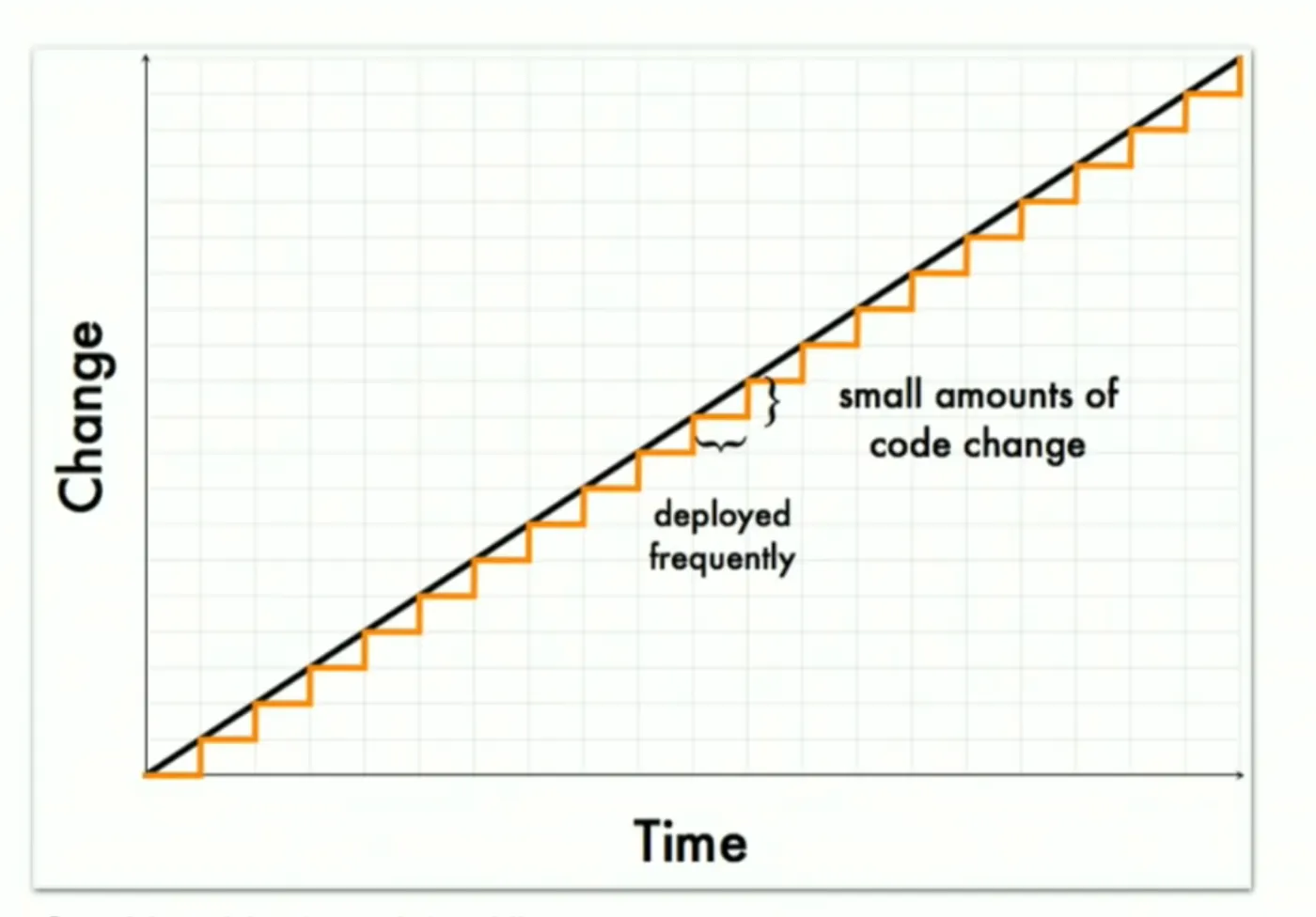

Small, frequent deployments with continuous integration reduce risk and enable faster feedback

Small, frequent deployments with continuous integration reduce risk and enable faster feedback

Video Reference: Sam Newman’s excellent talk “Feature Branches and Toggles in a Post-GitHub World” provides deeper insights into why trunk-based development and frequent integration are superior to long-lived feature branches.

Conclusion

Two fundamental truths about merge conflicts:

- Conflicts cannot be made to disappear—the earlier we resolve them, the better

- Semantic conflicts cannot be captured by diff tools—write automated tests and exercise human judgment

The fear of merge conflicts shouldn’t drive us toward isolation. Instead, it should drive us toward better practices: continuous integration, trunk-based development, and frequent, small changes.